Quelle: https://hpathy.com (18. April 2020)

Homeopath Siegfried Letzel discusses the cholera epidemic of 1831 in Europe, prior to modern medical knowledge, and Hahnemann’s insight into the disease and development of an effective approach to treating it.

These days will be entered in the history books as the “Corona Crisis” – less from the medical but rather from the economical point of view. With all the constraints and sacrifices the broad society is suffering, the focus now is on improving medical care by providing a sufficient number of intensive care beds and medical ventilators. It will be interesting to know how the scenery was at the time when modern scientific medicine had not evolved.

Epidemics, pandemics and infectious diseases in general always existed in human history. Bacteria and viruses were unknown, and also, hygiene, which today is a matter of lifestyle. Predominantly in urban areas, particularly during the ‘bad’ times – like during wartime, infectious diseases were permanent companions of human life.

At the times when plagues were raging, all the hopeless people were desperately exposed to them. Physicians tried to help their patients with all different kinds of therapeutic method, but mortality rates were unbearably high.

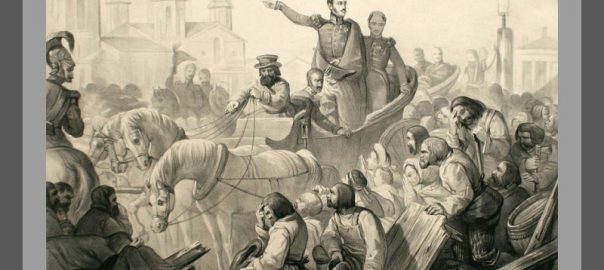

The same was the case in 1831, when a murderous epidemic came over Europe from Russia (about 2,00,000 victims) with tremendous speed and mortality. The Baltic countries, Poland (1100 deaths in Warsaw alone) and Galicia were already affected. In Prussia and Austria frontiers were closed and quarantine facilities were constructed. Nonetheless, the Asian Cholera could not be halted.

With their ignorance, physicians were helpless. Venesection had been a very common mode of treatment, leeches and cupping glasses were in use, but also medicines like calomel (a poisonous mercury preparation). During those days, this medicine had been the main emetic and laxative and it was found in virtually every doctor’s bag. We know that in most of the therapeutic attempts, patients got further debilitated, making matters worse. A ‘Pharmacopoea anticholerica’ (a pharmacopoeia with medicines against Cholera) listed 238 descriptions of medicines, all being ineffective according to the present knowledge.

During this time of agony and despair it was the Torgau citizen, chemist, pharmacologist and physician Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, founder of homeopathy, who published his therapeutic approach in four papers. He presumed that the so called cholera miasma consisted “of a living creature of murderous nature hiding from our senses”.

According to the investigation by philosopher Fechner, out of 54 researchers he had listed, only Samuel Hahnemann suggested the presence of microbes. He was the only one getting close to the cause of the disease.

Hahnemann remained faithful to the principle he adopted by treating cholera in a fixed manner as a ‘fixed disease’. This is to say that he treated patients with common symptoms with the same remedy. With his ‘therapia magna sterilisans’ he recommended as the very first physician camphor spirits as a medical drug – but also as a protective and disinfecting agent – an application against the threat of being infected with cholera. In advanced stages of the disease he suggested homeopathic remedies depending on the symptoms.

With this he was ploughing a lonely furrow. The treatment recommended by Hahnemann proved to be exceptionally precious and successful. Even medical authorities had to recommend his procedure unwillingly.

But Hahnemann even thought beyond this, in order to rule out further contagion and dissemination: he asked all people in quarantine and those who mingled with patients to “expose their clothes etc. to the heat of a baking oven of 80° C (176° Fahrenheit) for two hours. ( He meant that this will be the heat by which all known contagious matter and therefore also living miasms will be destroyed). At the same time their bodies will get cleaned by swift washing and covered with clothes of pure linen or fustian (thick cotton wool) from the facility.”

This had been utterly revolutionary in medicine at that time.

Considering the fact that Hahnemann had no microscope at his disposal like modern scientists, nor any personal contact with cholera patients (he was in Koethen then), so that he had to rely only on descriptions of the disease and of symptoms from friends and students, who he asked for information, it is virtually amazing that he could point with such firmness and certainty to the cholera miasm as a “living being of low order, which is hidden from our natural senses”.

And how could he have this insight with all certainty of a contagious property of the disease, spread by personal interaction? Based on this concept he developed his remedies which were strikingly effective according to the circumstances at the time.

In this way the cholera epidemic of 1831 led to a soaring approval of homeopathy. It developed in Torgau during the years of 1805-1810, and is now practiced worldwide, essentially without modification.

Siegfried Letzel

Curator, Hahnemann Exhibition,